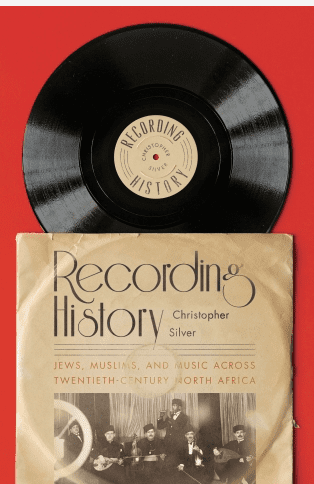

Music remembers much of what history has forgotten, says Canadian assistant Professor of Jewish history Christopher Silver, who has just brought out his book ‘Recording history’, a fascinating journey through the soundscape of North Africa before decolonisation. It was a vibrant era which produced the singing sensation Habiba Messika; Jews and Muslims played together. Jewish musicians made such an impact that Jews had broadcast time allotted to them on Radio Tunis between 1919 and 1956. The MacGill Faculty publication interviewed Silver:

We asked Professor Silver to share his insights on his research and how his new book contributes to the scholarship on popular culture and music in North Africa

Q: You launched Gharamophone.com in 2017 to preserve North Africa’s Jewish musical past. What inspired this archival project and how has it shaped the research behind this book?

In 2009, I had the good fortune of stumbling upon a record store––selling actual records––in Casablanca. Upon entering, the proprietor provided me with an unparalleled education in music. We spent quite a bit of time together listening to vinyl from the mid-twentieth century. After nearly every spin, he made sure to mention that the artists in question hailed from the country’s once sizeable Jewish community. Intrigued, I bought some records and then quickly grew curious about the recording industry’s origins in Morocco and across North Africa.

I began to gather brittle and yet remarkably durable early 20th century shellac records (10-12 inches in diameter, played at 78 rotations per minute) – from flea markets and online auction sites like Ebay. In the process, I built an archive that transformed my thinking about North Africa and the Jewish-Muslim relationship therein. Wanting to return this music to the soundscape, I launched Gramophone, a portmanteau of the Arabic “gharam” (love or passion) and the English “gramophone.” After decades of dormancy, the records uploaded thus far have been listened to more than 200,000 times.

Q: Why was it important to cover the history of North African music and its recording history?

Sound recording constitutes one of the most monumental technological innovations of the modern period. And it was a global phenomenon, even in its earliest years at the end of the nineteenth century. Indeed, if we want to understand why the present sounds like it does––musically or otherwise––then we must listen for the past. This includes excavating the origins of the recording industry in North Africa. With the rise in popularity of the phonograph at the turn of the twentieth century through the end of French rule in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia at mid-twentieth century, hundreds of thousands of records flowed across colonial borders in the Maghrib.